by Kerry Kollmar

July 23, 2009

I was introduced to a disc for the first time on sunny spring day in 1968. I was fourteen years old, enjoying a day out with my brother, Richard. He was twelve years my senior something of a hero to me, a familial shadow figure who popped in and out of my life all too infrequently. I was excited to be with him as we headed out to Central Park

Dickie carried with him an orange Pro model Wham-O Frisbee, gold bands hot-stamped in a smooth break between the concentric ridges which began just outside of the round black and gold label that stuck to the top of the cupola and ran to the outer edge of the top of the disc. The small, softly sinking crater of the nipple was visibly depressed from wear at the very center. I flipped the disc over, running my fingers over the raised lettering and read the legend under the copyright information:

Flat flip flies Straight. Tilted flip curves. Have fun, experiment!

Dickie showed me the main throw he knew, the underhand flip, and I tried, as best I could, to emulate what he did. As I watched him throw, it fascinated me that, although the disc left his hand clearly at an angle, it somehow righted itself every time. We tossed the disc back and forth as we walked through the park, passing through the Mother Goose playground where I'd played as a child, apple and cherry trees coming into full bloom outside its wrought-iron fences. I did my best to emulate my brother's throw, with relatively little success at first, but the flight of the thing had me spellbound. Dickie showed me the cross-body backhand throw next and I had slightly better luck with it.

We made our way through the playground, down the stairs on one side of the large dome that was the Bandshell and over the octagonal bricks in front of it, then across the park drive to the old ornate stairs that led down to Bethesda Fountain. Looking down as we descended, we saw perhaps two dozen young people standing across from each other, in two lines of eight or so on each side, long haired boys and girls, engaged in what appeared to be a furious battle with no less than a half dozen Frisbees, all blazing simultaneously across the two rows at speeds that seemed, even from our viewpoint, frightening. It appeared to be a gang fight, a mutual execution by consent, but in the case of this war all the soldiers were laughing hysterically and rather than avoiding the projectiles being hurled at them with what seemed like demonstrative aggression they willingly tried to intercept them, sometimes successfully, often not.

"Come on" my brother said and we walked down the stairs, carefully avoiding being bombarded by the discs. We stood out of range on the edge of the battle, watching breathlessly and eventually, summoning the requisite courage and joining in.

The game we'd come upon turned out to be the Central Park version of "Guts" Frisbee, of course, the disc sport most notoriously propagated by the beer-swilling roughnecks in Michigan and other parts the Midwest. Over a decade before we hippies thought we'd invented it, aficionados had held the well-organized IFT, an annual tournament built around the extreme sport of guts.

I found myself going back to the park, day after day, risking limbs if not life, until I could stand my ground with and against the best of the best players at the fountain, sustaining less than severe injuries from time to time, but along the way falling in love with that piece of orange plastic that would eventually become my life's passion.

There was, of course, more to do with a Frisbee than using it as a weapon, as I found out before long. I discovered that there were many different throws and catches and tricks that one could do. I worked intensely on mastering them all. I found myself constantly excusing my constant presence in Central Park and what had become a hopeless addiction to what became known as "freestyle" Frisbee. As best I could describe it, it was taking all of the various throws and catches and combinations thereof, and putting them together in the most fluid, flowing manner.

There was, of course, more to do with a Frisbee than using it as a weapon, as I found out before long. I discovered that there were many different throws and catches and tricks that one could do. I worked intensely on mastering them all. I found myself constantly excusing my constant presence in Central Park and what had become a hopeless addiction to what became known as "freestyle" Frisbee. As best I could describe it, it was taking all of the various throws and catches and combinations thereof, and putting them together in the most fluid, flowing manner.

There were a core group of players who became impassioned of Frisbee more or less to the same degree as I had and we showed up every day, regardless of weather, despite concerts or other gatherings no matter what and played. We started getting good. We became able to hit our tricks consistently. I had always been athletic, had participated in all of the sports normally associated with school and camps: soccer, baseball, tennis, water skiing and many others, and I'd excelled at most all that I'd attempted. I had never, however, felt the sense of freedom and intensity and control that Frisbee gave me.

We claimed an area of grass up the hill from the Fountain and it became known as Frisbee Hill (later moving a couple hundred yard to the southwest). Sometimes we jammed in front of the Bandshell and we began drawing crowds of onlookers, people who would form circles around our jams, sometimes, three, four, five people deep, and watch us, inspiring us deeper into that Zen-like zone that one aspires to in all sporting endeavors.

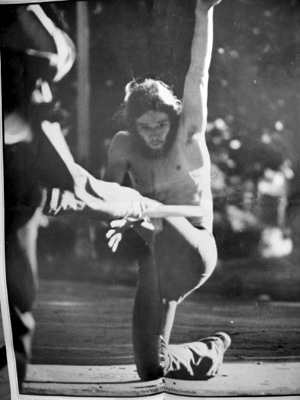

We played and played and discovered tapping (tipping to some), which prolonged the combination and, if done smoothly in creative sequences, was a real crowd-pleaser. It was one of the first evolutionary steps that brought freestyle beyond just throw/catch, throw/catch into something more. Kicking was yet another incarnation of the tap, again raising the level of play by increasing the difficulty.

New players showed up and watched and learned and grew, adding their unique abilities and tricks and styles to the growing Central Park Frisbee scene. It seemed that each player added something new and unique to the whole that we were. It was, if not a Frisbee "Think Tank", then a "Play Tank", where everyone, in addition to their individual purpose of personal growth, had the desire to see the whole scene and sport grow and blossom. Like electrical cords, all plugged into the same power socket, we drew energy form each other, shared it all with each other, gladly, with great joy at being part of this growing piece of gaming history. It was important to us, this thing we were doing and we could sense it growing and spreading in our wake.

Before long Joey Hudoklin and Ritchie Smidts, two amazingly talented players who were the core of the Washington Square Frisbee Wizards, began showing up and jamming with us. In incredible player, Joey would sit for hours, watching me play, always quietly respectful, occasionally joining me to jam. Little did I know back then the god-like level of play he would achieve, and the selfless mentor and advocate of the game that he would later become.

Before long Joey Hudoklin and Ritchie Smidts, two amazingly talented players who were the core of the Washington Square Frisbee Wizards, began showing up and jamming with us. In incredible player, Joey would sit for hours, watching me play, always quietly respectful, occasionally joining me to jam. Little did I know back then the god-like level of play he would achieve, and the selfless mentor and advocate of the game that he would later become.

Younger players, with the added advantage of the clean slate of their youth learned from us and learned quickly. I had grown into somewhat of a leadership role with regard to the Frisbee scene and greatly enjoyed the opportunity to work with new players. Peter Bloeme, a martial artist who's style reflected his intimacy with kata, came in young and learned amazingly fast, eventually inventing several staples of freestyle, including adding tricks like the Triple Fake to his already impressive repertoire. Mark Dana, his background in dance, brought his moves to scene and integrated them in graceful, flowing style.

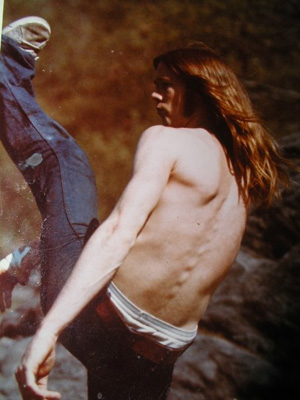

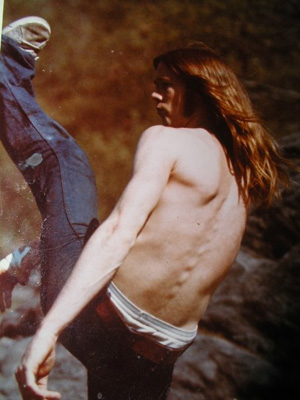

Krae Van Sickle, whose father Ken both played with us and chronicled in brilliant photography much of the Central Park Frisbee scene, came upon the scene very young. Krae and I bonded very quickly both as friends and players and I had the privilege of not only partnering with him on occasion, but of nurturing his game and watching as he evolved into one of the greatest players I've ever witnessed; his grace, creative elegance and natural effortlessness with a disc, in my opinion, surpassing us all. Both Peter and Krae went on to win both Junior and Senior World Championship titles in consecutive years.

At some point in the first part of 1974 a guy named John Kirkland showed up on Frisbee Hill and watched us play. He told us that he was a scout of sorts for Wham-O, the folks who we were well aware brought us the little plastic plates that we were so fond of flinging, and that there was going to be an event in August of that same year, to be held in the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California. Players from around the world, he told us, would come and compete in what would be the first World Frisbee Championships. He wondered if this would be of interest to us. Indeed it was.

We discovered, through John, that there was a circuit of tournaments happening all over the country and that in order to qualify for participation at the World Championships, one had to prove ones proficiency by scoring X amount of points at various tournaments. To say that this news made me happy or excited, well, you can imagine. In addition to bringing us the good news, John also shocked us with his level of pay. He was intensity personified - smooth, crisp, and an incredible showman. Our eyes, watching John's level of proficiency, began to open.

Still, we players in Central Park, knowing nothing of the commensurate grass roots ground swelling of Frisbee communities across the rest of the world, presumed that we were without a doubt, the finest players on the planet. Those of us who considered ourselves "good" figured we'd go to a tournament or two, take them by storm and wait for our Rose Bowl tickets to arrive in the mail.

As it turned out, there was a little bit of reality, waiting for us out there on the circuit.

Later that year, we would go to our first tournaments, one at Rutgers University and another at St. John Fisher College in Rochester, New York, where we were spoon-fed a large helping of humility. Oh yeah, sure we were good. But, it became clear to us, we were far from alone at the top of the heap.

By the summer of 1974, I was good at this sport called Frisbee. But I was far from satisfied with my level of play and, knowing that I had work to do in order to land myself at the Rose Bowl in August, I worked hard to improve my game. I went to the park every day, sometimes as early as mid-morning, hoping to find a partner, but knowing that even alone, as long as there was even a little bit of wind, I could practice TRC, MTA and distance throwing.

One morning, alone in Sheep's Meadow, I was exercising my solitary skills. I began tapping the disc, facing into the wind, the sun causing me to wince. At one point, as a gust of wind got under the front lip of the disc, I misjudged the tap, my second finger going up as the disc rose along with it, then the disc gently touched down on my finger and spun there for a couple of seconds.

One morning, alone in Sheep's Meadow, I was exercising my solitary skills. I began tapping the disc, facing into the wind, the sun causing me to wince. At one point, as a gust of wind got under the front lip of the disc, I misjudged the tap, my second finger going up as the disc rose along with it, then the disc gently touched down on my finger and spun there for a couple of seconds.

Something had occurred that had probably happened to me and a thousand other people a million times in the past. But, for whatever the reason, curiosity kicked in and I tried to duplicate it. Generating spin (via the underhand snap-back technique that I used to generate z's when practicing tapping) and, after several tries, was able to do it again. And again. I went home later that day and stayed up nearly all night, in my apartment, throwing it up and trying to spin it on my nail over and over and over until I could, with the help of the cupola's underside to keep it centered, do this new balancing act consistently. And so it was born. Purely accidental but undeniably large, I had no idea that day, that the whole nature of the game would be forever altered by that simple mistake.

Later the same year, and once again alone in Sheep's Meadow, I was going for a catch (I think it was either during TRC or possibly MTA practice) and the disc bounced away from my had, but rather than just drop to the ground, it maintained it's spin and levelness of attitude as it moved away from me into the wind. It occurred to me that there was more to be done with this mistake. I immediately threw a simple, lightly tossed backhand into the wind,

about head high, stepped toward it and slapped the left edge with the fingers of my right hand. It stayed fairly stable as I stepped toward it again and once again slapped the edge, knocking it awkwardly and losing control. Once again, after practicing over and over, chasing throughout the Meadow, I got to control it. Once again, I'd been fortunate enough to discover something that really added to the sport.

I'm certain that these discoveries would have come along eventually, stumbled upon by someone, somewhere at another time. I just happened to be the fortunate one. Indeed I've heard that Spider Wills (or was it Tom Bode?) had the Air Brush happening on the beaches of the West Coast pretty much simultaneously to my discovery on the East Coast. Doesn't really matter, as long as we share.

We began traveling to tournaments around the United States and, in 1979, to the European National Championships in London. The community of players was the same wherever we went; welcoming, lovely people wherever we went, everyone in it just for the jam. We all shared what we learned. Competition was stiff, but it was secondary to the shared, communal experience. It never seemed particularly difficult to accumulate the requisite points to get to the Rose Bowl each August. If you expanded your play to include the field events (MTA, TRC, Distance), and worked on your overall abilities (distance, accuracy, etc) in addition to whatever your specialty might be, you could accumulate enough points. My first World Championships in 1974 was unforgettable, just for the experience of being there with the best of the best. I think I took 3rd place overall, but I might as well have won for how great it felt. When I won the World Individual Freestyle Frisbee Championship title in 1975, you could have knocked me over with a feather.

As time went on, I experienced some incredible things as a result of my participation in the world of flying discs. I walked out to the park one morning to discover that a casting session was in process in the middle of Sheep's Meadow. They were looking for Frisbee players to cast in a Pepsi Commercial. There was a bunch of good looking young actors who knew nothing about Frisbee, trying to get parts in this commercial. It was to be aired nationally, debuting during the halftime festivities of the 1979 Superbowl. I walked over and stood near enough to the casting session that they'd have no choice but to see me and I began doing nail delays and air brushes. They called me over, asked me to do a series of simple tricks and eventually cast me (and Peter Bloeme) in the spot.

I met and played Frisbee with an incredible array of amazing people, including John Belushi and the cast of Saturday Night Live, Joe Namath, Kareem Abdul Jabar, Jackson Brown, Astronaut Mike Collins, Jerome Robbins (Choreographer of West Side Story and many other notable shows), and many, many more. It was the magic of the disc that attracted these people to me. And talk about an ice-breaker for meeting girls!

There were many reasons that I eventually drifted away from playing Frisbee full time. Although there was a period during which my income from disc related activities was enough to support me, that period was fairly short lived. I was offered several other opportunities that I couldn't afford to pass up and life eventually lured me in other directions. By the mid-70's I was producing and hosting three Cable Television shows, working at Rolling Stone magazine, then traveling with Art Garfunkel on a forty city tour of the U.S. and Canada and later working on the production staff of Musicians United for Safe Energy, producing five nights of concerts at Madison Square Garden. So I guess you can say life got busy and it was hard to pay the rent with Frisbee.

My daughter Molly, now fifteen years old, has recently developed a love for the game and, after a visit to my old stomping grounds in Central Park last summer, an awe of the evolutionary path of the sport. As have I.

I am absolutely knocked over at the level of play that exists these days. It's incredible and so exciting to watch from the perspective of one who, all those years ago, was awed by the simple capacity of that piece of plastic to fly the way I told it to do.

But the truth about Frisbee is that its greatest gift is not just enjoyed by those of us who have mastered it, but also reflected in the joy that it brings to people the first time they try it. Watch a child throw a Frisbee for the first time and you'll see what I mean. In its simple, miraculous design, Fred Morrison gave the world a universal tool for communicating. Everyone, everywhere speaks the language of Frisbee:

Flat flip flies Straight. Tilted flip curves. Have fun, experiment!

(c) 2009 Kerry Kollmar

Kerry Kollmar can be reached at kerrykollmar (at) hotmail.com or through his Facebook page, http://www.facebook.com/frizwhisperer

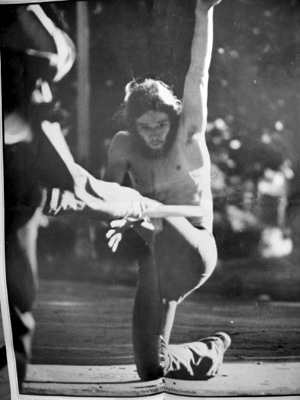

(picutred from left to right: Krae Van Sickle, Peter Bloeme, Mark Danna, Kerry Kollmar, Steve Vitilo, Dr. John Pickerill, Jens Velasquez, Erwin Velasquez)

There was, of course, more to do with a Frisbee than using it as a weapon, as I found out before long. I discovered that there were many different throws and catches and tricks that one could do. I worked intensely on mastering them all. I found myself constantly excusing my constant presence in Central Park and what had become a hopeless addiction to what became known as "freestyle" Frisbee. As best I could describe it, it was taking all of the various throws and catches and combinations thereof, and putting them together in the most fluid, flowing manner.

There was, of course, more to do with a Frisbee than using it as a weapon, as I found out before long. I discovered that there were many different throws and catches and tricks that one could do. I worked intensely on mastering them all. I found myself constantly excusing my constant presence in Central Park and what had become a hopeless addiction to what became known as "freestyle" Frisbee. As best I could describe it, it was taking all of the various throws and catches and combinations thereof, and putting them together in the most fluid, flowing manner.

Before long Joey Hudoklin and Ritchie Smidts, two amazingly talented players who were the core of the Washington Square Frisbee Wizards, began showing up and jamming with us. In incredible player, Joey would sit for hours, watching me play, always quietly respectful, occasionally joining me to jam. Little did I know back then the god-like level of play he would achieve, and the selfless mentor and advocate of the game that he would later become.

Before long Joey Hudoklin and Ritchie Smidts, two amazingly talented players who were the core of the Washington Square Frisbee Wizards, began showing up and jamming with us. In incredible player, Joey would sit for hours, watching me play, always quietly respectful, occasionally joining me to jam. Little did I know back then the god-like level of play he would achieve, and the selfless mentor and advocate of the game that he would later become.

One morning, alone in Sheep's Meadow, I was exercising my solitary skills. I began tapping the disc, facing into the wind, the sun causing me to wince. At one point, as a gust of wind got under the front lip of the disc, I misjudged the tap, my second finger going up as the disc rose along with it, then the disc gently touched down on my finger and spun there for a couple of seconds.

One morning, alone in Sheep's Meadow, I was exercising my solitary skills. I began tapping the disc, facing into the wind, the sun causing me to wince. At one point, as a gust of wind got under the front lip of the disc, I misjudged the tap, my second finger going up as the disc rose along with it, then the disc gently touched down on my finger and spun there for a couple of seconds.